El culebrero

(1998)

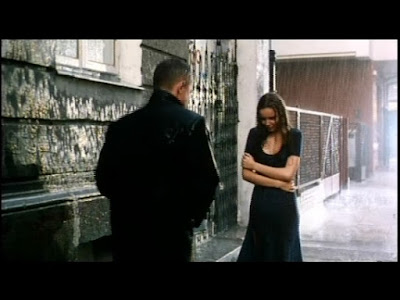

Here is the story of a drunk layabout, clad all in black,

who shares a special affinity with snakes.

He is being followed, as he stumbles throughout the film, by a

strikingly beautiful woman, also clad completely in black. Stiglitz plays a powerful land baron with a

wealth of affectations: cigar, glass of

tequila, faithful dog always at his side, wheelchair, and oxygen tank. Yes, Stiglitz is disabled in this one, but

his character is full of piss and vinegar.

A decent fellow lives in the shadow of Stiglitz’s hacienda with a small

farm, accompanied by his lovely wife and teenage daughter. He needs Stiglitz to cut him a break. The drunk layabout kills a few of Stiglitz’s

peeps. Then, purely by accident, the

drunk layabout witnesses the death of Stiglitz’s weed dealer by heart

attack. He brings the corpse to the

local police station, and when Stiglitz sees his dead homey next to the drunk

layabout (still clad in all black), he is certain that he is the killer. The decent fellow, who needs Stiglitz to give

him a break, is recruited by Stiglitz to kill the drunk layabout. He cannot bring himself to do it, because,

after all, he is a decent fellow and the drunk layabout is an okay guy. So, Stiglitz has his henchman kidnap the

decent fellow’s wife and daughter to force him to kill the drunk layabout. The two men have a showdown, but the

strikingly beautiful woman, also clad completely in black, intercedes; and the

decent fellow and the drunk layabout join forces to rescue the women and take

down Stiglitz. If this synopsis does not

make a lot of sense, then that’s cool.

El culebrero is a

modern-day Western with some odd themes thrown in. In a signature shot, the drunk layabout gets

ambushed by some of Stiglitz’s hitmen.

He feigns death, and as the hitman search his horse basket, they find a

bundle of snakes. One of the hitmen

kills the snakes with his automatic rifle.

The drunk layabout loses his shit, subdues a nearby hitman, grabs his

weapon, and kills the entire group of assailants. The drunk layabout keeps a snake inside of

his shirt, like a pet, and at opportune times, he pulls snakes from his pockets

and wields them like weapons. The

strikingly beautiful women, also clad completely in black, appears almost in a

supernatural role, like the guardian angel of the drunk layabout. Stiglitz yells at people; drinks tequila,

smokes cigars; and sucks oxygen from his tank.

El culebrero is definitely

weird, yet it is nothing special for Stiglitz fans.

La noche de la bestia

(1988)

Stiglitz and four of his homies go to a secluded shack for a

hunting party. On the first day, there

is male bonding, hunting, drinking, more drinking, and more male bonding. On the second day, after a morning of

hunting, Stiglitz and his homies see a beautiful woman running on the shore of

the lake, with armed pursuers following in a jeep. The beautiful woman and her pursuers are all

wearing the same yellow jumpsuit. One of

Stiglitz’s homies gets shot, and the rest of his crew kill the pursuers and

rescue the woman. They bring their

injured homey inside along with the woman.

They tend to his wounds, and the woman collapses from exhaustion. Stiglitz and his homies are in possession of

an operational automobile. Do they go

the police and report this incident? No.

First, let’s back up.

During the opening shot of La noche de la bestia, the yellow-jumpsuit-ed team packs some TNT

into the side of a mountain and detonate their bomb. They remove a large clump of glowing

ore. During the second night of the

hunting party of Stiglitz and his homies, they go outside the shack when they

hear a loud explosion. Over the horizon,

with state-of-the-art special effects, they witness a nuclear explosion. They chalk it off to the doings of the

locals. The following day the shootout

occurs. Stiglitz stays with his injured

homey, the beautiful woman, and another homey in the shack. The other two homies take the vehicle and drive

towards the explosion. They encounter a

shack where yellow jumpsuit-ed body parts and torn limbs are strewn about. They take the computer from the shack and

return to the hunting party. The dude that gets shot stumbles outside to get a

bottle of whiskey from the vehicle. He

goes missing, as something comes rising out of the lake to munch upon him. Stiglitz stays with the beautiful woman, as

the remaining bunch go looking for their injured homey. The beautiful woman, now conscious, requests

a shower. She comes out of the bathroom

and seduces Stiglitz. They do the

nasty. When the remaining hunting party

returns, they find the woman dead and Stiglitz possessed. Stiglitz tries to kill his homies, but they

put him down. They have an encounter,

then, with a monster.

I am not a big fan of male bonding and drinking, especially

with the inclusion of firearms; so the first have of La noche, is fairly pedestrian.

Its highlight is a scene evocative of the “dueling banjoes” sequence

from Deliverance (1972). La

noche really starts cooking when the group encounter the beautiful woman

running along the shore of the lake.

Then, La noche adopts the

skeleton narrative of John Carpenter’s The

Thing (1982) and becomes a decent, B-movie, sci-fi/horror film. It is worth noting that the DVD version of La noche de la bestia that I watched

appeared censored: the audio would drop

out periodically (presumably to remove profanity); the shower scene of gorgeous

Lina Santos appears abbreviated; and the pivotal scene of Stiglitz and Santos

doing the nasty is absent (it is rare that a B-movie would have its viewer

infer an important plot point and avoid sensationalism.) However, as food for thought, La noche de la bestia is very violent

with its violent scenes seemingly intact.

This one turns out pretty cool and an addition to the syllabus for the

serious Stiglitz student.

Traficando con la

muerte (2001)

The first half of Traficando

con la muerte, you can file under “fuck yeah!” Stiglitz plays a drug-addicted, seriously disturbed

individual who practices voodoo; worships the devil; and kills people. He looks like a hooded corpse. In the opening scene, Stiglitz snorts some

coke and says some mumbo jumbo in his dilapidated shack. He goes outside and hooks up with two chumps. They climb aboard a big rig and hit the road

(they are trafficking drugs). The police

set up a roadblock, but Stiglitz tells his chumps to drive through it. Stiglitz and the chumps disembark from the

semi and engage in a firefight with the police.

Stiglitz shoots the lead police officer and spares his life, only after

giving him a grimacing smile. They are

the only two to survive. Subsequent to

this shootout, the surviving police officer begins to have hallucinations of

Stiglitz. Is it Stiglitz voodoo or

PTSD? I do not know, but the police

officer is forced into medical leave until he is better. Stiglitz attends a rodeo, and after a fight

with her boyfriend, a very beautiful woman gets seduced by Stiglitz’s mumbo

jumbo. He takes her back to her home,

and the two do the nasty. The woman’s

boyfriend shows and catches the two in bed.

Stiglitz ices the man and sweetly kisses the woman goodbye. The local drug dealer needs some more drug

trafficking via big-rig trucks, so he sends two chumps to Stiglitz’s

shack. One of the two is rather plump,

so Stiglitz disembowels the man, so the narcotics can be fit inside. They cross the border with a coffin in the

back of the big-rig truck. The police

quickly allow them to pass. At this

point in Traficando, Stiglitz has

pissed off quite a few people who come gunning for him. Stiglitz finds a homey, drinks tequila, and

snorts cocaine. The final shootout is

eminent.

In Traficando,

Stiglitz plays a truly evil character whose services are for purchase. (“Dirty deeds done dirt cheap,” as the saying

goes.) The second half of the film

forces its story into a traditional action film which offsets the coolness of

the first half. I really preferred just

watching scary Stiglitz go around performing evil acts without purpose. The first half is essential exploitation

cinema, and overall, Traficando con la

muerte is well-worth seeing for the Stiglitz fan.